British Evacuees in World War Two

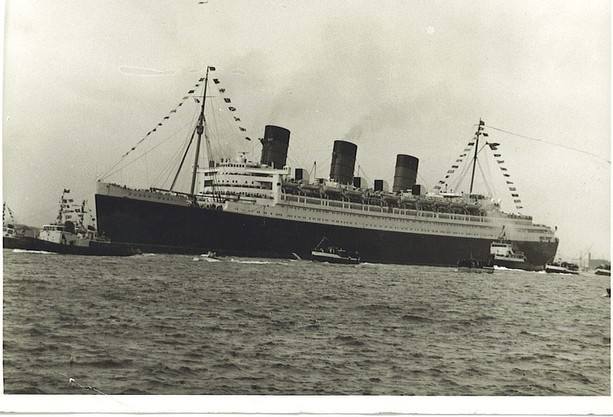

The Queen Mary, seen above in Southampton Water on the occasion of her final voyage, was used as a troop carrier during World War II

British Evacuees of World War II

When the Second World War broke out in September 1939, the British government had already given considerable thought to evacuating civilians from the big cities. The lessons from the Spanish civil war were there for all to see, and the authorities had a detailed evacuation plan already in place.

In fact, the first evacuations began in June 1939, three months before war broke out, although the first official movement of civilians did not start until September 1st 1939, just two days before the declaration of war.

From London and the other main cities such as Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield, Glasgow and Birmingham, priority class persons (consisting of children, pregnant women, mothers with infants, and the disabled), boarded trains and were duly transported to rural towns and villages throughout England, Scotland, and Wales.

My mother was an evacuee. She was fifteen when the war began and was moved from the Wirral peninsula out to Anglesey, a remote (it certainly was then) island off the north-west coast of North Wales. The family she stayed with spoke Welsh as their first language, indeed they only ever spoke Welsh unless they were speaking to the evacuees, and though they treated my mother well, she always said it was a very lonely time for her.

Evacuees were gathered into groups at the main railway stations and were often put on the first available trains almost regardless of destination, which must have made the housing of them at the other end immensely difficult. Some went by sea too, paddle steamers took many children from Dagenham to East Anglia.

In all, 3.7 million people were moved, and it has been estimated that one in three of the entire British population was directly affected in some way by the evacuations. In the first three days of the official evacuation a staggering one and a half million people were transported from their homes to the countryside, the biggest mass migration of British people ever in such a short period of time.

Of these, approximately 800,000 were children of school age, 500,000 were mothers with young children, plus 12,000 pregnant women and 7,000 disabled persons. To help look after them, over 100,000 teachers and other helpers were also required to relocate.

Beyond that, a further two million people, mainly the more well to do, arranged a private evacuation of their families, settling in rural and remote hotels for the duration of the war, while several thousands took themselves further away from any possible bombing raids by moving to the United States, Canada, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand and the Caribbean.

Some, such as the unfortunate passengers on the S.S. City of Benares did not reach their destination. (See my article: The Children of The City of Benares), and the merits of sending children overseas during wartime has been debated ever since.

Today, there is a flourishing association of the Evacuees, they have taken to marching in the remembrance parades, and who could deny them the right so to do?

You can read about some evacuees who were sent overseas during World War II on the ship The City of Benares here