Grist Vergette Excerpt

Grist Vergette's Curious Clock

Excerpt From The Book

Chapter One

Grist Vergette passed away on the two hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar. He died peacefully, slumped in the armchair, the Daily Telegraph well read and neatly folded at the obituary column, perched on his lap. The importance of the date would not have been lost on old Grist for he was a navy man through and through. He was also a man of many secrets, and they all died with him, until now.

Grandson, Johnny Vergette, was lying on his back in the garage. He was tinkering with an old 125cc motorbike that had once belonged to his father. His hands were splashed with oil that had fed to the red checked shirt that had also once belonged to his dad. Johnny discovered it in the airing cupboard pressed senseless under the weight of clothes above. The shirt was so old fashioned it was now cool. Johnny liked it anyhow. He couldn’t wait to be seventeen when he could ride the bike on the highway, but that was still two long years away. When you are fifteen it can seem an interminable wait to become an adult. You can almost see the Promised Land, practically smell it, but you can’t touch it, daren’t touch it, and sometimes you wonder whether it will ever truly arrive.

His mother hustled through the utility room and opened the internal door that led to the garage and cooed softly, ‘Johnny, can you come inside a moment, we need to talk to you about something very important.’

‘In a minute,’ he replied, just about keeping the teenage angst from his voice.

‘Now,’ she said, a little more firmly this time, and he began to wonder what he might have done to upset the old folks.

He hauled himself to his feet, wiped his hands on a piece of dirty towelling, an action that only served to spread the muck around still further, and loped from the garage and into the house.

They were sitting at the kitchen table, or at least his mother was. His dad was standing behind her, his hands on her shoulders, like a pose from a family photograph from long ago. Thankfully, neither of them appeared unduly upset, though Johnny still wondered if they had discovered the half dispatched bottle of Scotch whisky that lay beneath his tee shirts in the bottom drawer in his bedroom cupboard. He didn’t particularly like whisky, hated it in fact, but he’d bought it, and hidden it, and drunk some of the content, just because he could. True he was still only fifteen, though he looked much older, taller and broad, and he had little difficulty in buying feisty gear in the off licence. Old Abdul would always serve him in there with a smile and a joke.

Sometimes Johnny bought stuff for his mates too, but his parents didn’t have to know about that, they didn’t have to know about any of it, about lots of the things he did, they mustn’t. Not a chance. It was none of their damned business.

His father comfortingly half smiled, and Johnny smiled back. What was this queer episode all about?

‘Sit there will you, son,’ he said, pointing to the chair opposite his mother.

Johnny languidly sat down and his mum turned her head away and looked up at dad. He nodded, as if she should start proceedings, and then she turned back to face her little boy, who no longer was so little.

‘You know your granddad died,’ she began softly, as if suddenly finding something rivetingly interesting on the table in front of her.

‘Yeah,’ he said slowly. Odder and odder, he thought. ‘We went to the funeral, right? Last month?’

‘Yes of course we did. Well, we received your inheritance in the post today. It came by special delivery from his solicitor.’

She pulled a blue plastic envelope from her pinny pocket and cradled it just above the surface of the gleaming table.

‘My inheritance?’ he said, glancing down at the skinny envelope. It didn’t look much, he couldn’t help thinking, but old Grist was always full of surprises.

‘Yes,’ she said, and she pulled something from the envelope and laid it in the centre of the table. It was a key, and a large key at that, long, silver, and thin. The handle was a complete oval with a hollow centre, and the business end comprised three quite separate jagged teeth that looked at if they had been yanked from a crocodile.

‘A key?’ he said.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘A key.’

‘That’s it?’ he said. ‘My inheritance? From granddad? An old key?’

‘Yes,’ she repeated. ‘It belongs to his shed, down on the allotment.’

Johnny couldn’t contain a laugh any longer.

‘He left me his garden shed?’

‘Yes,’ she confirmed.

‘He left me his garden shed in his will?’ he repeated, incredulously.

His mother bobbed her head. ‘He was most insistent that only you should have it, and that you should go there by yourself. Heaven only knows why.’

‘I knew he was a bit barmy, but this is crazy.’

‘He was your granddad,’ said father quickly. ‘He had his own ways of doing things. Yes, he was a little eccentric sometimes, but he was very good-hearted, as you well know, and very clever too. Don’t think too badly of him, John. We’d like you to go down there and take a look around.’

‘Now?’

‘Why not? There’s no time like the present.’

Johnny Vergette nodded and grunted and grinned at his parents. They grinned back.

‘OK, if that’s what you want,’ and he reached across and picked up the key and squeezed it into the back pocket of his dirty, black jeans.

‘Good! That’s settled then,’ said his mother.

She seemed strangely uptight about the whole business.

‘I have to clean the bird,’ she mumbled, and she fled the room to fiddle with the cockatoo in the conservatory, something she often did when she was nervous or confused, or troubled, or uptight about anything, though it was difficult to tell which applied here.

Johnny stood up and made his way to the door. He had to pass his father to leave the room. His dad clasped Johnny’s wrist and tugged him closer and whispered in his ear. ‘There’s two thousand pounds for you too, son. Just don’t tell your mother, OK. I thought we could get you a proper bike sometime.’

The lad glanced at his father and saw the conspiratorial look set on his face like a smirking mask. Johnny nodded and smiled; they both did, as if sharing vital secrets that only the menfolk must know.

‘Thanks dad, thanks.’

‘Don’t thank me, kid; thank your granddad. It’s all down to him.’

Johnny grinned again and ambled out through the door.

‘No worries then,’ his dad shouted after him. ‘Go on, son, and I hope you find something good,’ and with that his father closed the front door behind him.

The Vergette’s lived in a neat red brick Edwardian detached house. It had been built in the 1920’s long before car ownership was commonplace, and it had remained in the Vergette family ever since.

Garages and drives hadn’t been thought of back then, but between them and the house next door, they had constructed their own driveway that was just about wide enough to let a vehicle pass between the buildings, where they could park in safety around the back. The Vergettes had added their own garage ten years before and the drive itself was shared with the neighbours, the Streckers. They were German, the Streckers, but nice enough for all that.

Mister Strecker was a regional manager for a cheap German supermarket group. He was in charge of all their branches in Surrey and Hampshire, but his mother still referred to him as That grocer next door. Grocer or not, it didn’t stop Johnny casting a covetous eye over Mister Strecker’s beautiful silver Mercedes Kompressor sports car whenever he had the opportunity. That day it was missing, the car, because it was Saturday morning and Mister Strecker would probably be fussing over the shoplifting figures in some utilitarian supermarket in the poorer suburbs of town. Business was booming, apparently, at the discount palaces, so they said, credit crunch and all, and the car seemed to prove the point.

The Merc might have been missing but his daughter wasn’t. Her name was Seri, short for Serilda, and she was walking up the drive toward their house beneath the large oak tree that had grown far too big for the road. Seri was fifteen too, and tall, just like Johnny was, and her long blonde hair bounced happily as she walked toward him. He noticed that well enough.

She smiled at him confidently through her neat blue eyes, and Johnny smiled back. In the sunshine she looked really cool, nothing like her usual image of loose fitting Nike and GAP grey and beige gear, topped with the obligatory baseball cap. That day she was wearing a smart green dress, and that was really unusual. He could rarely recall seeing her wearing a dress before, and he could never remember her looking like that before.

‘What’s with the dress, kid?’

‘Don’t you like it?’

‘It’s cool, but why?’

‘Been to have my photo taken. Mutter made me wear it.’

For a moment they stood awkwardly together, each wondering what to say next, and when they did speak, they did so at exactly the same time.

‘Where you going?’ she said.

‘Must be off,’ he said.

They smiled awkwardly again and then he said, ‘My granddad left me a key in his will, can you believe it? The old ragamuffin. The key to his old shed down on the allotment. I’m going down there now to see what treasures await.’

She smiled politely as if to say, that’s nice, and she wondered if that was an old tradition in England, and then he said, ‘Don’t suppose you’d like to come along?’

She grinned again, broader this time. ‘OK, why not? Nothing better to do.’

‘Do you wanna get changed or something, it might be a bit dusty down there.’

‘Nah. Better not,’ she said. ‘If I go inside mutter will make me stay for lunch and tidy my room.’

‘Your mum sounds like my mum.’

‘All mums are the same,’ she said. ‘It’s what mothers do, I guess.’

‘Come on then,’ he said, ‘it’s not far.’

They walked along the tree-lined avenue and turned left past the Ring O’ Bells and on toward the big red brick school.

‘Is this an old English custom?’ she teased. ‘The grandfather leaving the grandson the key to the shed on the allotments?’

Johnny laughed roughly. ‘Not that I know of, I’ve never heard of anything like it before. It’s really weird, don’t you think?’

She nodded again, but she wasn’t surprised because the English were a truly weird race, but oddly likeable, for the most part. The girls at school had always been most friendly towards her, and in the four years she had been there she had never experienced any anti German sentiment.

They passed the school and after that a row of twenty or so semi-detached houses, and beyond that the allotments began.

They were divided from the road by a tall wire fence, the wire occasionally covered in climbing plants; clematis, honeysuckle, Russian vine, and where it wasn’t, the fence had grown rusty. Inside, two or three old guys were busy at work lovingly tending their plants. Beyond them, a middle-aged woman was pulling up onions as a Westie dog sat obediently before her, staring down, seemingly knowledgeably, at everything she did.

The entrance to the allotments was at the far end of the wire fence where there was a rickety wooden-framed gate that had warped and split. Every time it had been opened and closed it had dragged across the concrete and over time it had worn a deep rut in the path, and now the rut was a darker colour to the rest of the cement.

Johnny carefully opened the gate, holding it higher to clear the rut, as Seri stepped through, and he closed it behind them.

Granddad’s allotment was as far away from the road as it was possible to be. It was tucked down in the bottom corner, bordering the public playing fields. The ground there was shaded by an old laburnum tree that granddad had often cited as his excuse as to why his carrots and parsnips were never quite as good as the competition’s, though it didn’t seem to bother him unduly. Fact was, he didn’t seem that interested in gardening, and he was usually to be found thinking of other things. or tinkering away in the shed.

But not that day, for he’d gone now, forever.

An old guy approached them pushing a wheelbarrow full of steaming horse muck.

‘Oi!’ he yelled. ‘What are you kids doing in here?’

There had been a lot of trouble with kids coming on to the allotments after dark, drinking and worse, breaking into some of the sheds, spraying inane graffiti every which way, leaving nasty items behind. Kids were unwanted in these parts, kids were the sworn enemy, but Johnny recognised the old man. It was mad Harry Fawcett. Harry was one of granddad’s best pals, but everyone knew he was as shortsighted as it was possible to be; yet he still adamantly refused to wear spectacles. After all, he’d reached seventy-eight years of age without wearing bloody eye-glasses, as he referred to them, and he blimmin well wasn’t going to start wearing them now.

And anyway, he liked Rosie Berisford in the Ring O’ Bells, he liked her a lot, even though she was thirty years younger than him, and he imagined that she would cease to like him, if overnight he transmuted into a four-eyed geek.

‘It’s me,’ shouted Johnny, ‘Johnny Vergette.’

Harry set the wheelbarrow carefully down and squinted and breathed out.

‘Oh sorry, John, I didn’t recognise you. What are you doing here?’

‘Granddad left me his key,’ said John, and he brandished the key as if to confirm the point. ‘To the shed, down there.’

‘You going to keep the allotment on, John?’

‘Don’t know yet, Mister Fawcett, don’t really see meself as a gardener somehow.’

‘You should you know, son. That allotment has been in the Vergette family for nearly a hundred years. Your granddad’s father had it before him you know, and probably his father before that. Once you give it up, you’ll never be able to get it back. Like gold dust they are. You keep hold of it, kid.’

‘I’ll think about it,’ said Johnny, not realising until then that so many of his forefathers had toiled over that same piece of mucky shaded ground.

‘And who’s this then?’ he asked teasingly, looking at the pretty girl through widening eyes, as if he had noticed her for the first time.

‘She’s Seri, she’s our neighbour.’

‘Nice dress, Seri, pleased to meet you, don’t get mucky now, must be off, work to do.’

They watched him slowly wheel the squeaky barrow away before continuing down the path to the corner of the site.

‘Nice man,’ she said.

‘Yeah,’ grunted John, ‘he is.’

Granddad’s shed lay at an angle to the corner of the plot, but it wasn’t like any of the other sheds. It was larger and better constructed. It was made of hardwood, and granddad had maintained that building as if it were an ocean going sailing yacht. The shed was painted annually battleship grey; the roof was grey too, as if he had acquired government surplus paint from the dockyard down at Portsmouth. The shed had recently been thoroughly re-painted too, and like everything of granddad’s, it was in immaculate condition.

The heavy door bore traces of a boot print where some kid had tried to kick the door down. But the door was as solid as concrete, and the attacker had taken on more than he’d imagined. Johnny pictured the youth limping away from the scene, swearing madly; possibly nursing a broken toe. Serve the blagger right for messing with Vergette property.

They stood together in front of the door as he slipped the key into the huge padlock. He glanced at Seri and she looked back at him through widening eyes, willing him to turn the key. He was taking his time, but then he did so, and it slipped smoothly over with a gentle squeak. The lock fell away into his hand as he clasped the door handle and pushed it open. The door was heavy to the touch as it slowly opened inward with a queer creak.

Inside, it was dimly lit. Light was coming from two large windows, one on the far wall and one to the right hand side. But no one could see in from outside because the glass was opaque, like in a bathroom, and the windows were double glazed units too, and that seemed very odd to John. Who on earth double-glazes their garden shed? Just inside the door, to the right of the doorframe, was an old brown Bakelite switch. Johnny snapped it on more in hope than anything, but it fell down with an audible click, and high up amongst the cobwebs an unshaded bulb in the apex burst into life. It had worked perfectly first time and that was a surprise.

How had granddad fed power all the way down here? None of the other sheds appeared to boast mains power.

‘Come on in,’ Johnny said, and Seri stepped inside as he closed the door behind her.

‘It’s bigger than you think,’ she said.

‘It is, and neater too.’

It really was, dusty yes, but surprisingly neat and tidy, as if everything had been carefully set in its rightful place, as if granddad had known his time was nearly up, and he was leaving everything just so, for the benefit of those that followed.

Along the sidewalls was an assortment of cupboards and shelving units that had been borrowed from house clearances over the years, and in the middle of the large single room stood a long workbench. Some of the wall units were from long ago discarded kitchens; others were paint stained oak bookshelves that once might have looked pretty grand in the right location. They covered most of the walls, broken only by the windows, and a small free area on the left sidewall.

The free area was covered in posters and diagrams. Johnny approached and stared at the pictures that were drawing-pinned to the timber. But they were not garden posters, not details of what seeds to sow and where, but diagrams of merchant ships, and convoy routes, and silhouettes of warships and submarines, and pictures and stats on mines and ammunition, and depth charges, and hand drawn diagrams of cute looking bi-planes, complete with single machine guns poking out the front.

‘Look at that,’ he said, running his fingers over the outlines of long ago sunken merchant vessels.

‘What is it?’ Seri asked.

‘I don’t know. Something to do with shipping movements.’

‘So your granddad left you all this?’ she said, half jokingly, sweeping her hand round at the dusty boxes and tins and posters and cobwebs.

‘Yes,’ he replied eventually. ‘He did.’

‘But why?’

‘I have no idea.’

‘Do you think there’s anything here of any value?’

‘I don’t know, wouldn’t have thought so, but granddad was such a strange old sod, you never could tell what was on his mind.’

‘So what are you going to do now?’ she said, her hands neatly folded across her chest.

‘I’m going to look through all the boxes. See what I can find. Do you want to help?’

‘OK,’ she whispered, ‘might as well. It’s what Saturdays were made for.’

Johnny across glanced at her. That cute smile was still fixed on her face, and he liked her little joke.

‘Sure thing. Saturdays were made for this,’ he said, as he picked up an old tin and blew a thick layer of dust in her direction.

‘Oh Johnny!’

Chapter Two

In one corner of the shed was an old shiny-bladed lawnmower, though there was no lawn on the site, and next to that, five or six ancient garden tools, standing together like guardsmen. Like everything else, they were immaculately clean and maintained. The garden equipment commanded only a tiny portion of the space that existed there, almost as if they were present as an afterthought, as if there on sufferance. This was a shed whose primary purpose was clearly not for gardening.

Johnny yanked open one of the kitchen cupboards. They had been yellow once, but had now faded to a dull cream. The cupboard was full of nineteen-thirties engineering magazines, issue upon issue of them, all filed in strict date order, not a single copy missing, so far as he could see.

‘Look at this,’ said Seri, and she handed John an old rutted and chunky folding knife. Within the ruts, two sets of initials had been deeply impressed. GV, RN. Grist Vergette, Royal Navy. Johnny carefully opened it. The blade was shining Sheffield steel and razor sharp, and he didn’t dare run the tip of his thumb along it, for he knew well enough what would happen. He gingerly closed it, anxious not to shut it on his finger.

Next to that he found an old Crawford’s biscuit tin. It was almost a foot square and over time it had rusted. He eased off the lid and it vibrated loudly as it came away. Inside was a folded newspaper dating from the early nineteen forties.

He gently grasped the paper and set it down on the bench, as pieces fell away from the corner of the newsprint. It was decomposing before their eyes. After the paper there were black and white photographs of ships, old ships, some with three and four tall funnels. Some were merchantmen, others warships, and still others, merchantmen that had sprouted gun turrets and Bofors anti aircraft guns, hastily mounted on the superstructure.

On the reverse of the photos were pencilled written names. SS Rangoon. SS Singapore. HMS Dart. HMS Dainty. HMS Bullock, and all the notes were written in granddad’s perfect forward sloping handwriting.

Johnny recognised it immediately from the birthday card he always received bang on the nail every year, each card containing a crisp ten-pound note as if he had printed it that very day. Granddad may have been forgetful about some things, so they said, but he couldn’t have been that forgetful, for he never once missed Johnny’s birthday, and in future Johnny would miss that, and not solely for the money.

On the lowest shelf was a large wooden box. It was painted black, but not recently, as if it had been painted long ago. It was about eighteen inches square, and heavy, as Johnny found out soon enough, as he gently lifted it from the shelf and set it down on the bench.

‘Look at this,’ he mumbled.

Seri came and stood beside him. ‘What is it?’

‘I don’t know.’

The lid was about two inches deep and it was hinged at the back. On the front of the lid was a white ivory nameplate, but it was caked in dust. Johnny rubbed his thumb along it and they watched as black print beneath slowly revealed itself. Admiralty Property, it said, just those two words, curiously printed in longhand.

Johnny tried to open the box, but it was locked fast. In the centre of the front of the lid, just below the label, sat a large keyhole. It seemed to be inviting anyone with a key to try their luck.

‘It’s locked,’ he said, his voice betraying his disappointment.

‘Try the key,’ she said.

‘What key?’

‘The front door key,’ insisted Seri.

‘Don’t be thick! That won’t work,’ he said dismissively, trying hard to keep the irritation from his lips. Of course the front door key wouldn’t open an old box like this, only a girl would suggest such a stupid thing.

‘Try it,’ she insisted.

So he did, to keep her sweet, knowing full well it was a complete waste of time.

As easy as that, the lock flipped over.

It had turned over as smoothly as the front door lock had done. It had opened as if it were brand new, as if the best locksmith in the land had handcrafted it only yesterday.

Johnny could appreciate engineering work like that, for he had inherited the Vergette engineering gene. They shared a look, Seri’s a tad triumphant, he thought. He carefully raised the lid and stared inside. The box was full to the brim with treasures. Seri peered around his shoulder and gawped inside too.

‘Look at that!’ he said quietly, glancing back over his shoulder at the front door, as if suddenly worried they might be disturbed.

‘What is it?’ she said.

‘Medals!’ he said, removing a long string of decorations. One by one he counted them, pausing the tip of his finger on each. Twelve in all, and three of those had metal bars half way down the ribbons.

‘I knew he did things in the war,’ he mumbled, ‘but not all this!’

Then the thought occurred to him that Seri was, after all, a German.

‘The Second World War,’ he clarified.

‘I know,’ she said, ‘I’m learning English history too, I’m at your school remember, in your class, you don’t have to be defensive about the war with me.’

‘Sorry,’ he said. ‘Didn’t think.’

Next to the medals were dozens of brass naval buttons, each bearing different designs of anchors and twisted rope.

‘They’re sweet,’ she said, picking one up and breathing on it and rubbing it on his shirt.

Johnny grinned. Only a girl could describe buttons as sweet.

Five or six large photographs of Grist in uniform followed, pictures that Johnny had never seen before. Grist was smirking at the camera, in his prime, his dark eyes sparkling down the years, his peaked cap set at a jaunty angle, his hair poking out defiantly, sweeping across his forehead.

‘Is this him?’ she asked excitedly.

‘Yep. Sure is.’

‘He was gorgeous, wasn’t he? Just gorgeous!’

‘You think so?’

Johnny had never considered that his old granddad could ever have been described as gorgeous by anyone, or that he might have once been so, but what did he know? He could only remember the happy wizened face that had always been present throughout his life, peering into his cot, slapping his back, laughing, tickling him, always to be accompanied by shrieks of laughter, teaching him how to ride a bike, grinning through those expressive rheumy eyes, and later on, that slight tint of sadness that only ever comes with the years.

‘Oh yes!’ Seri insisted. ‘He most certainly was. Handsome! Like a film star!’

‘You think so?’

‘I do.’

There was another photograph of Grist, with a lady. She was wearing a thin patterned cotton frock, strangely not unlike what Seri was wearing now. She looked so proud, the lady in the picture, laughing back at the lens, laughing at the world, her long dark hair cascading down her porcelain neck, her eyes advising them, even now after all this time, that she knew she was living through her special years, and was determined to enjoy them to the utmost. How happy she looked. How happy they both looked.

‘That’s grandma,’ he said proudly. ‘She died more than ten years ago. I can only just remember her.’

‘She looks nice too,’ said Seri, taking a second peek at her intelligent face.

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘she was, everyone says so, they both were. Everyone said granddad really missed her after she’d gone.’

‘I’ll bet he did.’

Beneath the photographs were several manila foldover files. They each bore the Admiralty crest, but nothing more. Johnny took one out and set it on the bench. He blew away the dust and opened it. The paper within was ultra thin, almost like tissue paper. The text had been typed by an ancient typewriter where the ribbon had been well worn even on the day it had been written. Now the words had all but vanished, but the impressions were still readable, even where the print had faded to nothing.

The paper was dated October 1941 and across the top right of the sheet at an angle, a large red rubber stamp had been carefully laid. The red stamp hadn’t faded one bit, and it read: TOP SECRET.

‘Look at that!’ he said.

‘What does it all mean?’

‘I haven’t a clue, but it will be fun trying to find out.’

I’ll come back to those in a minute, he thought, because there were other interesting things that had caught his eye.

Beneath the files were a large number of silver coins. They were coins that Johnny didn’t recognise at all. Pre decimal coins, large and unwieldy, but strangely impressive for all that, almost like medals themselves. They were half crowns. A dozen of them in all, each bearing the likeness of a variety of British kings that Johnny couldn’t begin to name. He carefully set them on the bench beside the medals and the pile of treasure, his treasure, was slowly mounting up.

‘Are they worth much?’ asked Seri.

‘I don’t know, but dad will know.’

‘Are they silver, do you think?’

‘Could be.’

He took one and carefully bit it, though in truth he didn’t really know why. He’d seen winning competitors do that at the Olympics, and prospectors do that in old movies. Kirk Douglas always did it, but after the bite, Johnny hadn’t so much as marked the coin, and he didn’t know what that meant either.

There were some old pennies too, large single old coppers from long ago, some going back to Queen Victoria’s time, though not worth much today, but he slipped them into his pocket anyway. His dad would know for sure if they held any value.

Beneath the coins was a cloth-covered notebook. The cloth was beginning to come apart, loose strands hanging below like broken cobweb. Johnny carefully lifted it from the box as if it were an icon. He glanced inside. It was full of mathematical formulae, all written in granddad’s neat hand, all checked and rechecked, some ticked with a red pencil, like ancient school work, others crossed, a few neatly corrected, but all the figures and data baffled Johnny.

They baffled Seri too, and she was ace at maths, top of the year. If only granddad was still here they could ask him what it all meant, but he’d gone, and now they could never ask him anything, ever again.

‘What does it all mean?’ she repeated.

‘I have no idea.’

‘Why did he leave you all this weird stuff?’

Johnny shook his head. It was a good question. Why had granddad left these treasures to him, and not to his father, who was Grist’s only son after all? He had specifically left everything to Johnny, and the more he thought about it, the more determined he was to discover why.

Underneath the notebook was what looked like a puzzle board. It was folded over in the middle and held together with a strip of glued black cloth. He opened it and set it down on the bench. It resembled an old board game he had once seen called Battleships and Cruisers, a notion that was reinforced by the tiny metal ship shapes that next came from the box. They were hulls only; no superstructure, all different sizes with impressed numbers within the metal, as Johnny set them down on the squared board, and began prodding them round with the tip of his finger.

‘Is it a game?’ Seri asked, and she gently laughed.

‘I don’t think it is.’

‘What then?’

‘I think they’re plotting charts, back from the war. And look at these!’

He lifted two Morse code senders from the box. He recognised them from old black and white war movies he’d occasionally watch in the afternoons on TV when it was raining. He set one up and began tapping away.

‘Polar bear! Polar bear! It’s a secret code,’ he said, and he giggled like a little kid.

Seri laughed too because she liked him when he laughed like that.

Then he said, ‘There’s always been a story that granddad did something really secret in the war, but when we asked him about it, he always clammed up. He said it was so long ago, and that it wasn’t worth worrying about. It’s too late to ask him now, but I wish we had when we had the chance. I so wish we had. And I remember too, when we pestered him he always said, It wasn’t worth worrying about, but then sometimes he’d add but one day it might be! Just like that, he’d say: One day it might be!

‘You mean like today?’ she said.

‘Who knows, could be.’

Seri shook her head. ‘Your family are really peculiar, weird in fact, you know that?’

Johnny glanced across at her. Perhaps she had a point. He couldn’t think of anyone else at school who had ever been left a garden shed, and even if they had, they wouldn’t have been left a garden shed quite like this one. This shed was now Johnny Vergette’s shed, his personal property, and it was truly unique, and Johnny was beginning to enjoy the experience.

The box was almost empty with only a few items remaining. Next, he carefully removed a circular travelling clock. It was a little battered and covered in orange cowhide. She watched him examine it slightly disdainfully, and then he proceeded to sniff it.

‘What’s that?’ she asked.

‘An old clock, I think.’

He pressed the golden dimple on the edge of the rim, and the clock sprang open in his hand.

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘a crappy old clock.’

‘That’s not a clock,’ she laughed. ‘It’s got six hands!’

He glanced at the face. ‘So it has. That’s odd. Perhaps one’s for seconds, one’s the alarm, one’s for the month, something like that.’

‘It’s not a clock at all,’ she insisted. ‘It only goes up to ten, and the ten’s a zero.’

Johnny stared down at the green luminous digits. She was right. There were only ten numbers on the face, and the zero was where the twelve should have been. How come he hadn’t spotted that? Six hands and ten numbers, what on earth was it?

The gubbins of the clock, or whatever it was, came half way out of the case and sat on the rim exposing the rear of the workings. On the back were several tiny handles and Johnny began twiddling with them and the hands moved round randomly, but it never once deigned to tick. Johnny shook it gently, but it still didn’t tick. A harder shake. Nothing. Whatever it was, it was useless. Well past its sell by date.

‘It’s knackered,’ he said, as he set it heavily down beside the other treasures before returning to the box. All that remained inside were six old wristwatches. They were all men’s watches, chunky, heavy, ancient, one with cracked glass, and they seemed expensive to him. They looked as if they had been buried at the bottom of that box for more than half a century, which in reality, they had.

He wondered if they were there for a reason. He tried to wind the first one. Nothing. Knackered. Useless. Crap. But the second one started immediately with a loud tick tick tick and a bright face. He set it about right, strapped it to his wrist and showed it off.

‘Hey-hey, I’ve got a new watch. What do you think?’

‘It’s nice,’ she said. ‘Much nicer than those fancy coloured things you see today.’

Johnny nodded. She was right. The watch was cool, and he was the king of cool. He would wear it to school on Monday, especially as Seri liked it too.

The box was now empty so he picked it up and ran his hands around the base inside like a magician to show that it was clean. He smiled that infectious smile of his, triggering her to smile back. He puffed out his cheeks and ran his fingers through his newly trimmed dark hair and wondered what to do next. His hair was gelled and combed straight back because that was the way he liked it. Clean cut. Neat. Cool. Modern.

The alarm bell on the travelling clock burst into life.

Seri jumped. Johnny smiled and made toward it.

‘Well something is working anyhow!’

He slapped the top button and the alarm stopped, but more than that, the clock folded back within itself and closed up with a slick click.

‘That was neat,’ he said. ‘I wonder how it did that.’

‘It was really neat,’ she agreed, ‘cool,’ she said, staring down at the closed calf leather.

A noise began pulsing from the clock. Slowly at first, but gradually increasing in volume and rapidity. Vum……vum……vum.

‘What the hell’s that?’ muttered Johnny.

The gold rim that spanned the circumference, where the clock opened and closed, began glowing, and a moment later the rim began revolving, independently around the clock.

‘What the heck?’ muttered Johnny.

‘What is it doing?’ asked Seri breathlessly, unable to drag her bright eyes away from the hypnotic movement.

‘Search me, Ser. I have never seen anything like it.’

The pulsing sound increased still further in volume and rapidity, as did the brightness.

Vum! Vum! Vum!… Vum! Vum! Vum!

A moment later Seri said, ‘I’m starting to feel dizzy.’

‘It is warm in here,’ Johnny answered, ‘I’ll open the door.’

‘No!’ she said. ‘It’s not that! It’s the clock thing that’s making me dizzy. Can’t you turn it off, Johnny? Please turn it off. Turn the damn thing off!’

Johnny glanced across at the girl, and back at the clock. It was now glowing like molten gold, and he was beginning to feel a little woozy too.

‘I’m feeling terribly dizzy,’ she repeated. ‘I think I’m going to be sick.’

‘What the hell is happening?’ Johnny remembered saying to himself; and after that all he could remember was Seri repeating over and over again, her voice growing weaker each time:

‘I’m feeling terribly dizzy.’

‘I’m feeling terribly dizzy.’

‘I’m feeling terribly…’

He reached out and grabbed at the clock and as he did so, Seri fainted into his arms. Everything went black. He was dead to the world. They both were. Dead.

© TrackerDog Media and David Carter 2016

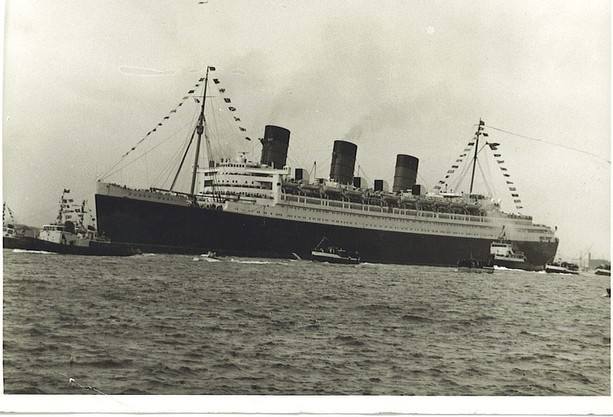

This is the RMS Queen Mary, above, photographed on Southampton Water on the occasion of her last sailing. Photo © TrackerDog Media

And this is the Southern Cross, possibly steaming somewhere off Africa.

Chapter Three

To read more of the incredible adventures of Johnny and Seri you will need to purchase the book. Buy in paperback or Kindle. Thank you for reading so far.

To read more about Grist Vergette's Curious Clock please click here or you can read a review on Grist Vergette right here

and here's the youtube booktrailer if you missed it before